technology facilitated abuse.

Technology Facilitated Abuse is is a form of domestic violence that provides abusers a pervasive way to control, coerce, stalk and harass their victims.

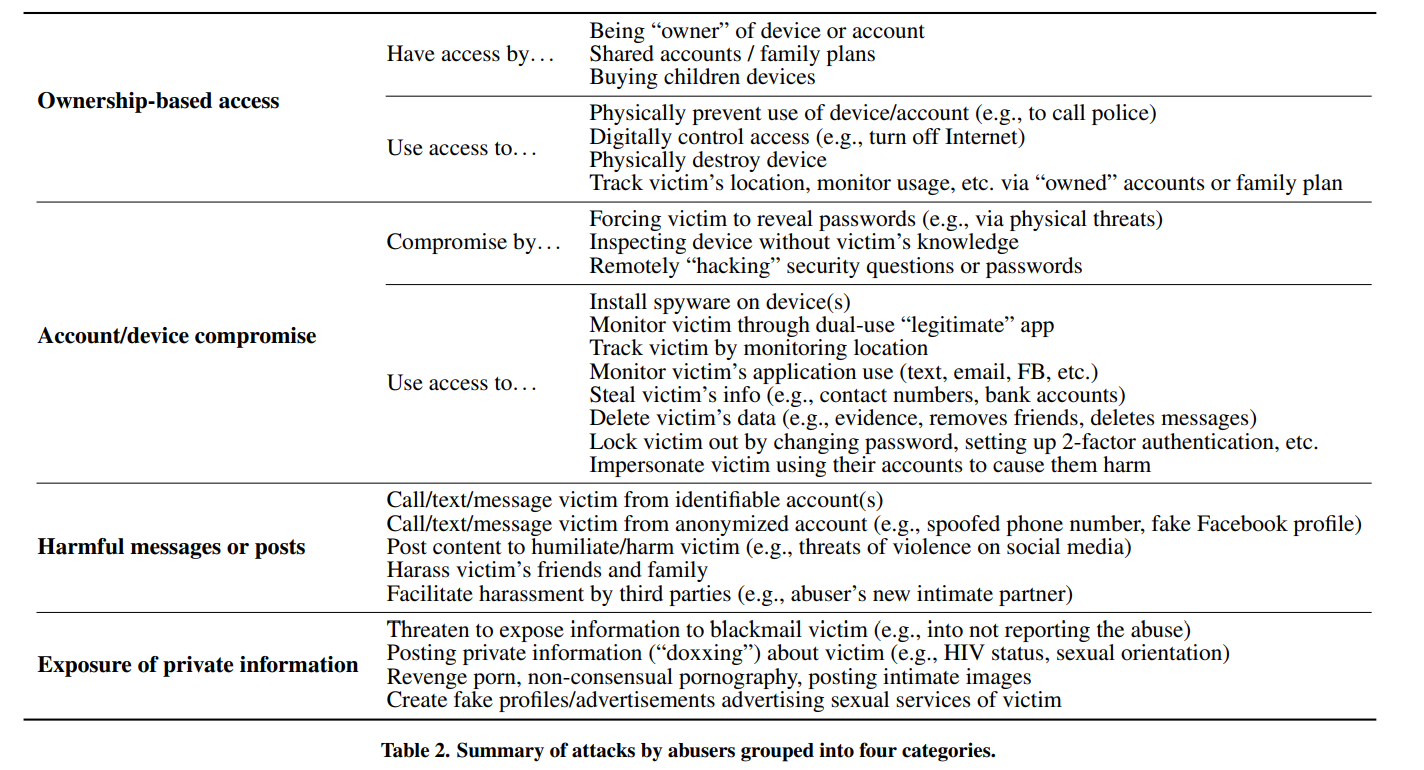

TFA includes a range of behaviours. These include sending abusive text messages or emails, making continuous threatening phone calls, spying on and monitoring victims through the use of tracking systems, abusing victims on social media sites, and sharing intimate photos of the victim without their consent (“revenge porn”). (source)

Technology Facilitated Coercive Control (TFCC) the abuse of technology in the context of coercive and controlling intimate relationships.1

Five of the most commonly used technology and online platforms by abusers are:

smartphones

mobile phone

social media

email

GPS tracking

Technology-facilitated abuse can involve perpetrators misuse of devices (such as phones, devices and computers), accounts (such as email) and software or platforms (such as social media) to control, abuse, track and intimidate victim-survivors. This abuse can be individualised, such as the perpetrator using threats that have specific meaning for the victim/survivors, but may seem innocuous to others.

It can also involve the use of technology by perpetrators to:

• post or send harassing or abusive messages

• stalk (tracking someone’s activities, movements, communications)

• dox (publish identifying, private information)

• engage in Image based sexual abuse (producing or distributing intimate images or video without consent)

• make or share clandestine or conspicuous audio or visual recordings of another person

• impersonate or steal another person’s identity

(source)

“the biggest threat to cyber safety is often women’s intimate partners and ex-partners.”

— Wesnet 2020 Report

in Intimate partner violence, the abuser and victim share an intimate relationship in the physical world as well. This changes the nature of the attacks and enables abusers to use their intimate knowledge of victims to inflict additional harm.

VIOLATION OF DIGNITY

The Australian eSafety Commission considers the following to be online harms that violate dignity;

Non consensual sharing of intimate material

Sexual extortion

Bullying, abuse, insults, rumours, social exclusion

Trolling

Cumulative or volumetric attacks

Non-consensual sharing of intimate material or image based abuse.

eSafety research conducted in 2017 indicates that while one in ten Australians will experience image-based abuse, some groups experience it at higher levels. For example, 24% of women aged 18-24 and 15% of girls aged 15-17 had experienced image based abuse (non-consensual sharing of intimate images).

Abuse of Women Through Tech

While technology is supposed to make lives easier, some people are abusing it to stalk and harass unsuspecting women through smart-home systems, location trackers, and spyware. This technologically-facilitated form of harassment is referred to as smart abuse, according to tech journalist Takara Small. Toronto lawyer Kate Robertson joins her and Nam Kiwanuka to discuss the legal implications associated with the misuse of these devices.

Australia case study : Wesnet 2020 2nd National Survey Report

Westnet findings indicated that men are the main perpetrators of technology facilitated abuse, and women the main victims, adding weight to the gendered nature of technology facilitated abuse.

The Wesnet report highlights the need for broader cyberbullying programs to recognise the gendered nature of technology-facilitated abuse.

2020 Report showed;

244.8% increase in respondents seeing perpetrators use GPS for tracking of victim-survivors

114.9% increase in the use of text messages, emails and instant messaging to surveil women

183.2% increase of the use of video cameras, create a climate of intense monitoring and surveillance.

perpetrator

motivations

According to self reported perpetration in a 2022 study by ANROWS the following were the motivations of perpetrators

Deactivation and reactivation of accounts – used by perpetrators to evade detection, reducing the ability for the victim to report an account and the ability for platforms to take action against account holders.

Multiple accounts – used by perpetrators to target an individual from numerous accounts or profiles.

Fake/imposter accounts – accounts set up under a false identity, generated manually by another person or generated automatically through the use of bots.

Pseudonymity – where perpetrators use a different name, term or descriptor to target and abuse another person in order to hide their identity.

Temporary accounts – accounts that are set up for a short period of time for the sole purpose of targeting/harming another person.

Resubscription of accounts – where old accounts are reactivated in order to harm or abuse another.

Changing account or profile details or identifiers – after engaging in abusive and harmful behaviour on platforms, perpetrators can quickly change their account or profile information or ‘unmatch’ or ‘unfriend’ their victims to avoid detection.

Switching between private and public platforms – this can be to escape the moderation of platforms as well as the intervention of bystander users.

Moving public conversations to private channels – this can be to escape the moderation of platforms, particularly through moving to forums that maintain end-to-end encryption (E2EE), as well as the intervention of bystander users.

Cross-platform targeting – where perpetrators target an individual from multiple platforms and devices in a coordinated manner.

Source: https://sbd.esafety.gov.au/

modes of abuse by perpetrators

Technology facilitated abuse and digital exploitation have not had the required level of awareness, recognition and state attention that is necessary to regulate content within Irelands contemporary society.

Despite the limited sources on Irelands digital presence, evidence shows there ‘were 4.95 million internet users in Ireland in January 2022 (Kemp (2022)